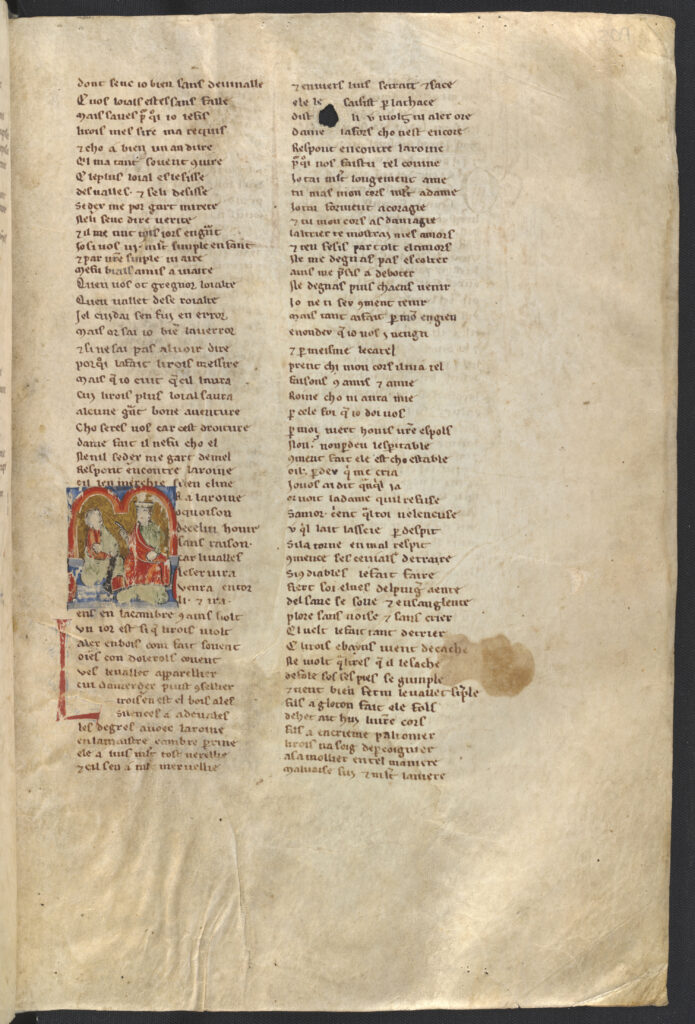

Sponsa Christi (Brides of Christ)

Artist: Unknown

(From a late thirteenth-century copy of William of Waddington’s Manuel des pechiez/Manual of the Sins)

Media: Manuscript Illumination (ink and pigment on parchment)

Date & Location: c. 1280, England

Where can I see this artwork?: Princeton Library, Special Collections, Taylor MS. 1, folio 44 recto (this whole manuscript has also been digitized for online viewing)

Significance to Queer Art History

Both men and women wrote passionately about their visionary experiences of Christ in the late medieval period. These accounts, and visualizations like this one in Taylor MS. 1, invite considerations about gay and lesbian relationships. What does it mean for a layman (non-clergy man) to fantasize an erotic embrace with Christ? Might we find pleasure in looking at this medieval image of two men embracing?

It also invites questions of gender fluidity. The union of a human soul with Christ was often allegorized as a bride-groom relationship. In cases of AMAB (assigned-male-at-birth) or masculine devotees, though, this results in a feminization. They become ‘the bride’ of Christ. Similarly, Christ’s body (and especially his wound) is often imbued with multiple genders. The wound might be also a vulva or a breast in the writings of the medieval mystic, and indeed is sometimes represented as giving birth to a personification of the Church.

He [Christ] tenderly placed his right hand on her neck, and drew her towards the wound in his side. “Drink, daughter, from my side,” he said, “and by that draught your soul shall become enraptured with such delight that your very body, which for my sake you have denied, shall be inundated with its overflowing goodness.” Drawn close in this way to the outlet of the Fountain of Life, she fashioned her lips upon that sacred wound, and still more eagerly the mouth of her soul, and there she slaked her thirst.

vision of Catherine of Siena (1347–1380)

Resource(s)

Karma Lochrie. “Situating Female Same-Sex Love in the Middle Ages.” The Cambridge Companion to Lesbian Literature, Cambridge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015. 79-92.

Robert Mills. “Hanging with Christ.” Suspended Animation: Pain, Pleasure and Punishment in Medieval Culture. London: Reaktion Books, 2006. 177-199.